Emily Chow Bluck

artist | educator | community organizer

Context

redlining: what is it?

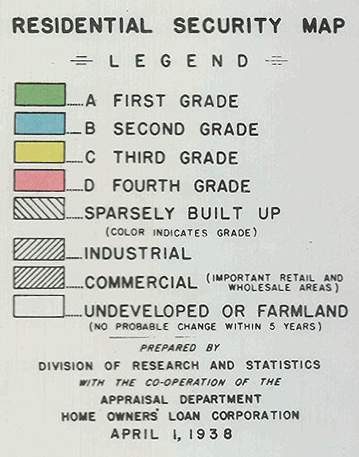

In 1935, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board asked Home Owners' Loan Corporation to create "residential security maps" for 239 cities across the United States that would denote their level of confidence in successful real-estate investments. Each city was segmented into four types of areas: Type A (Green) were the most desirable areas to lend to, Type B (Blue) were "Still Desirable," Type C (Yellow) were considered "Declining" areas, and Type D (Red) were treated as risky, "Undesirable" places to invest in, particularly for mortgage support. Neighborhoods outlined in red were often older areas of the city and disproportionately home to large populations of lower-income communities of color.[1]

These residential security maps were widely circulated in government and private real estate, financial, and banking sectors, but essentially hidden from public view.[2]

Although the historic impetus for redlining was to provide recommendations for banks as to where they should provide mortgages and other investments, this practice has led to a gross disinvestment in low-income neighborhoods of color. For Horizon Line, the interest is not simply to raise awareness of a historical racist practice, but rather to build a conversation around how the legacy of racism and classism in the United States has inadvertently had lasting implications on wealth inequity and neighborhood, business, and homeowner stability and displacement to this day.

contemporary relevance: gentrification, housing, and racial inequity

1. Gentrification:

"The impacts typically arrive too slowly, the changes too incremental to register on the lives they eventually affect."

-Gold, Daniel M. "Review: ‘Class Divide’ Shows the Extremes Hypergentrification Creates in a Neighborhood." The New York Times. 12 Apr. 2016.

2. Contract for Deed:

"From the 1930s through the 1960s, most African-Americans could not get mortgages because the government had deemed neighborhoods where they lived ineligible for federal mortgage insurance, the Depression-era innovation that made mortgages widely affordable.

"The situation exposed black families to hucksters who peddled homeownership through contracts for deed, in which a home seller gives a buyer a high-interest loan, coupled with a pledge to turn over the deed after 20 to 40 years of monthly installment payments. These contracts enriched the sellers by draining the buyers, who built no equity and were often evicted for minor or alleged infractions, at which point the owner would enter into a contract with another buyer. In the process, families and neighborhoods were ruined.

"Contracts for deed are making a comeback. They are increasingly being used by investment firms that have bought thousands of foreclosed homes and want to sell them to lower-income buyers 'as is,' according to a recent report in The Times by Alexandra Stevenson and Matthew Goldstein."

- The Editorial Board. "The Racist Roots of a Way to Sell Homes." The New York Times. 29 Apr. 2016.

Home Owners’ Loan Corporation residential security map, New York, 1938

Project Proposal

site | concept | materials | execution

Horizon Line is an installation and performance piece that investigates boundaries: both physical and perceived as well as the liminal space between the two. Using the history of redlining in New York City as a point of departure, Horizon Line interrogates how (un)intended racial and economic discriminatory government housing policies formed the groundwork for, and continue to contribute to present day gentrification, racial segregation, and discrimination. Gentrification is commonly talked about as a dynamic of upwardly mobile individuals renting housing in a lower-income community of color. The individuals' new presence in those neighborhoods is often cited as the instigator of rising rents, small business closures, and long-time resident push-out. Horizon Line intends to make visual a historic, pernicious policy while connecting that, now outlawed, policy to current discriminatory trends in neighborhood developments.

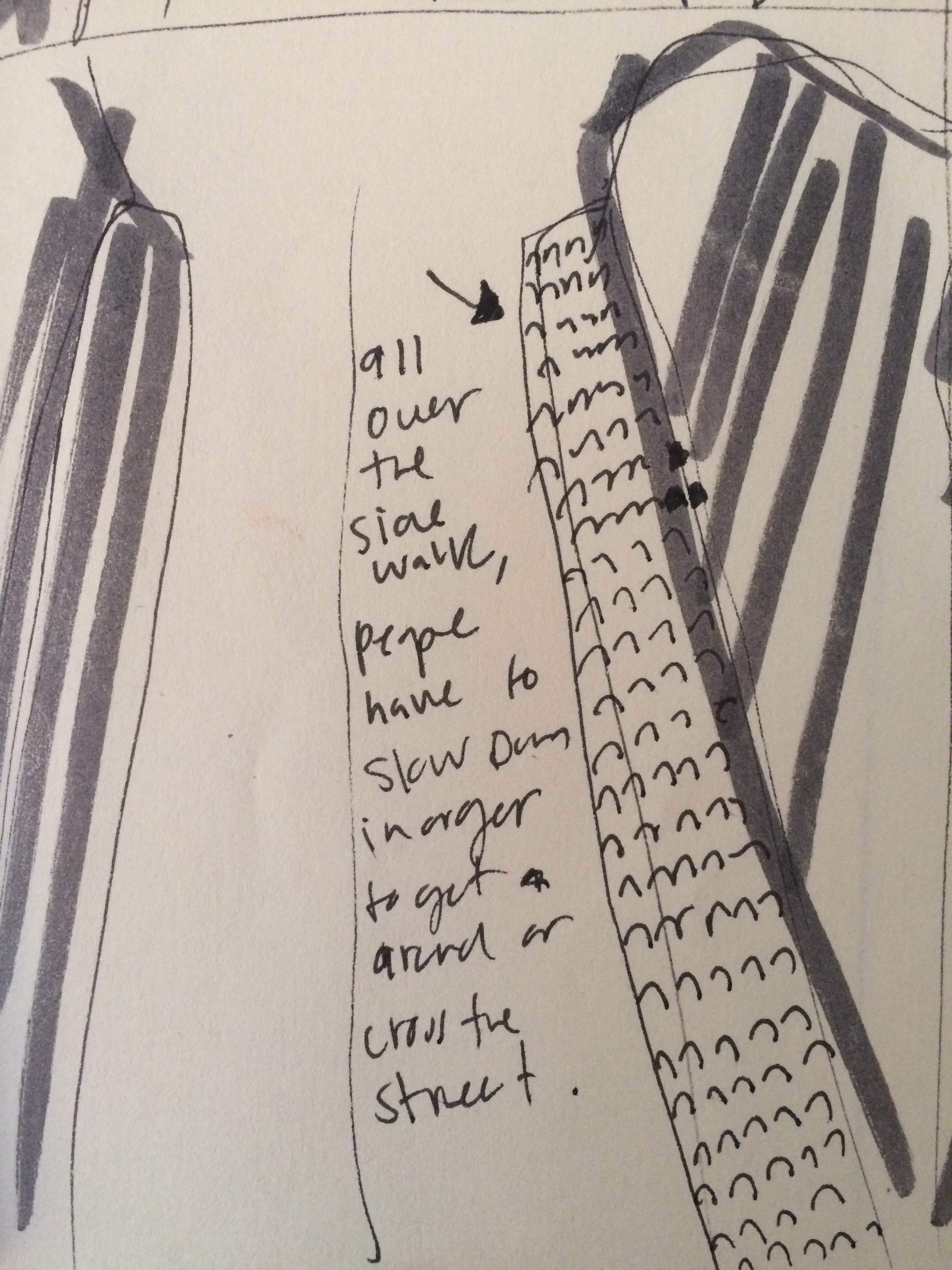

Artists Emily Chow Bluck and Jennifer M. Harley propose to create a visual boundary along (a) section(s) of 14th street. They will make a temporary 'redline' out of hundreds of pounds of brick dust along the site(s) of interest (the borders of neighborhoods historically redlined by the Home Owners' Loan Corporation) on 14th street. Furthermore, the artists will cast hundreds of small, New York City-styled brownstone buildings, each one standing approximately five to six inches high. These sculptures will be cast in paper pulp made of cotton and linen fibers—the same material used to make U.S. currency notes—in order to highlight how racial inequity is often achieved through maintaining economic inequality. The process of physically redlining the site and installing paper brownstones will be key performative elements of Horizon Line.

The materials that Bluck and Harley plan to use are crucial to the piece. Intending to underscore the perpetuity of downstream effects, the red brick line will certainly disappear, even if it is not deinstalled by the artists, while the paper brownstones will slowly degrade from natural weather occurrences. In this vein, although the original redline policy has disappeared, its lasting effects are evidenced in the discriminatory disinvestment from inner city neighborhoods, deterioration of local infrastructure, and the instability of communities and micro economies as neighborhoods grapple with new waves of gentrification. The viability of the paper brownstones is as much at the whim of weather as actual neighborhoods and their residents are to political and economic currents.

public engagement

Once the installation is complete, Bluck and Harley will hold and document dialogues with passersby about the public’s experiences with discriminatory housing practices, gentrification, and changes currently underway in their neighborhoods. The performative installation and subsequent dialogues will be documented by photo and video / audio recordings and posted online for public viewing and continued conversation.

Horizon Line, as it will occur on 14th street, will be the first iteration of an expansive, endurance performance that will be carried out by the two artists in historically redlined neighborhoods all across New York City.

U.S. currency notes are made from cotton fiber paper, the same material Bluck and Harley will use to cast miniature brownstones for Horizon Line.

Renderings, Sketches, & Animated Models

the redline

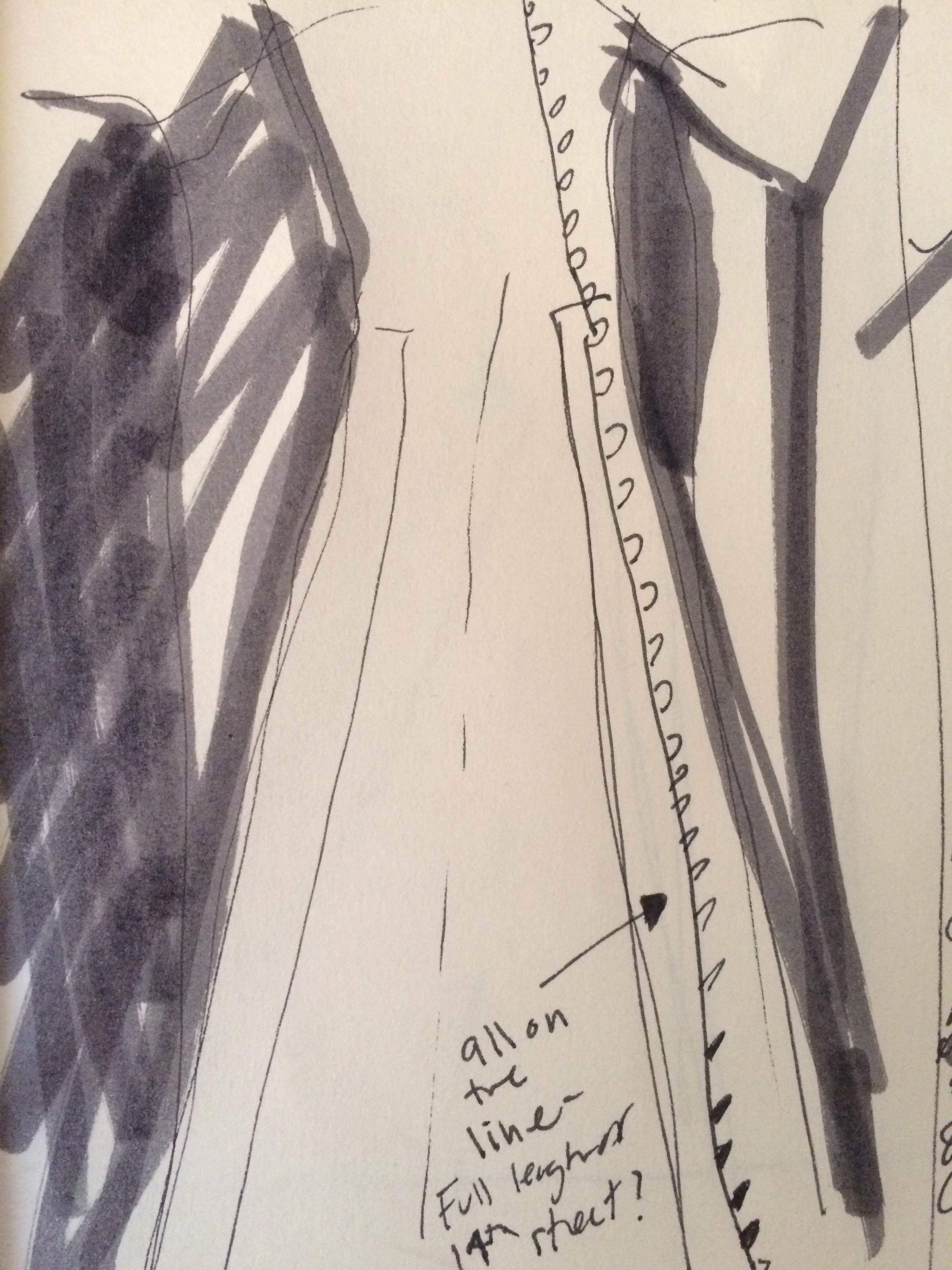

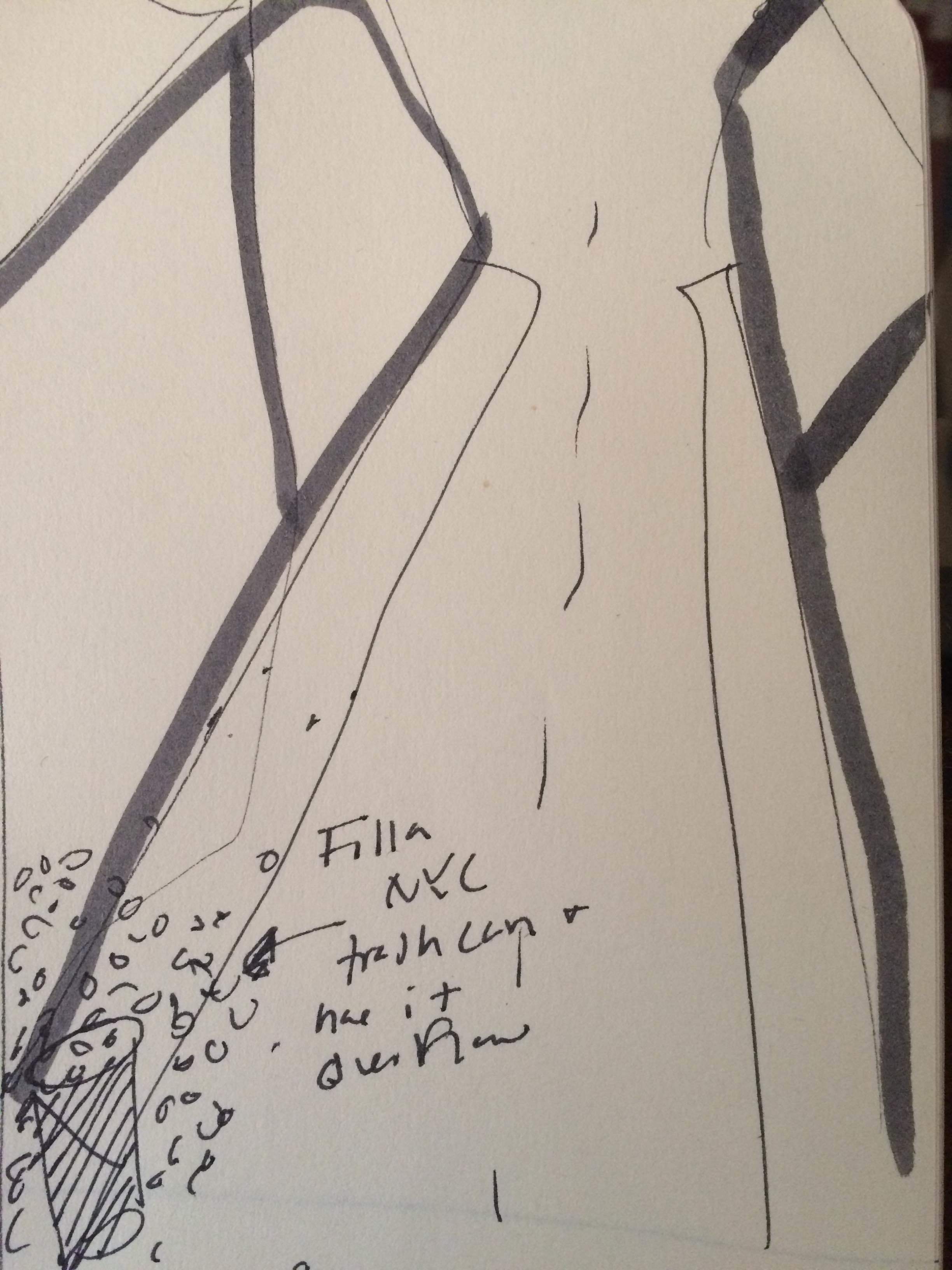

Rendering of a field chalker creating a redline of brick dust from east to west along the north side of 14th street at the 8th ave. intersection.

Rendering of a field chalker creating a redline of brick dust from south to north on the east side of 14th street at the 3rd avenue intersection.

brownstones

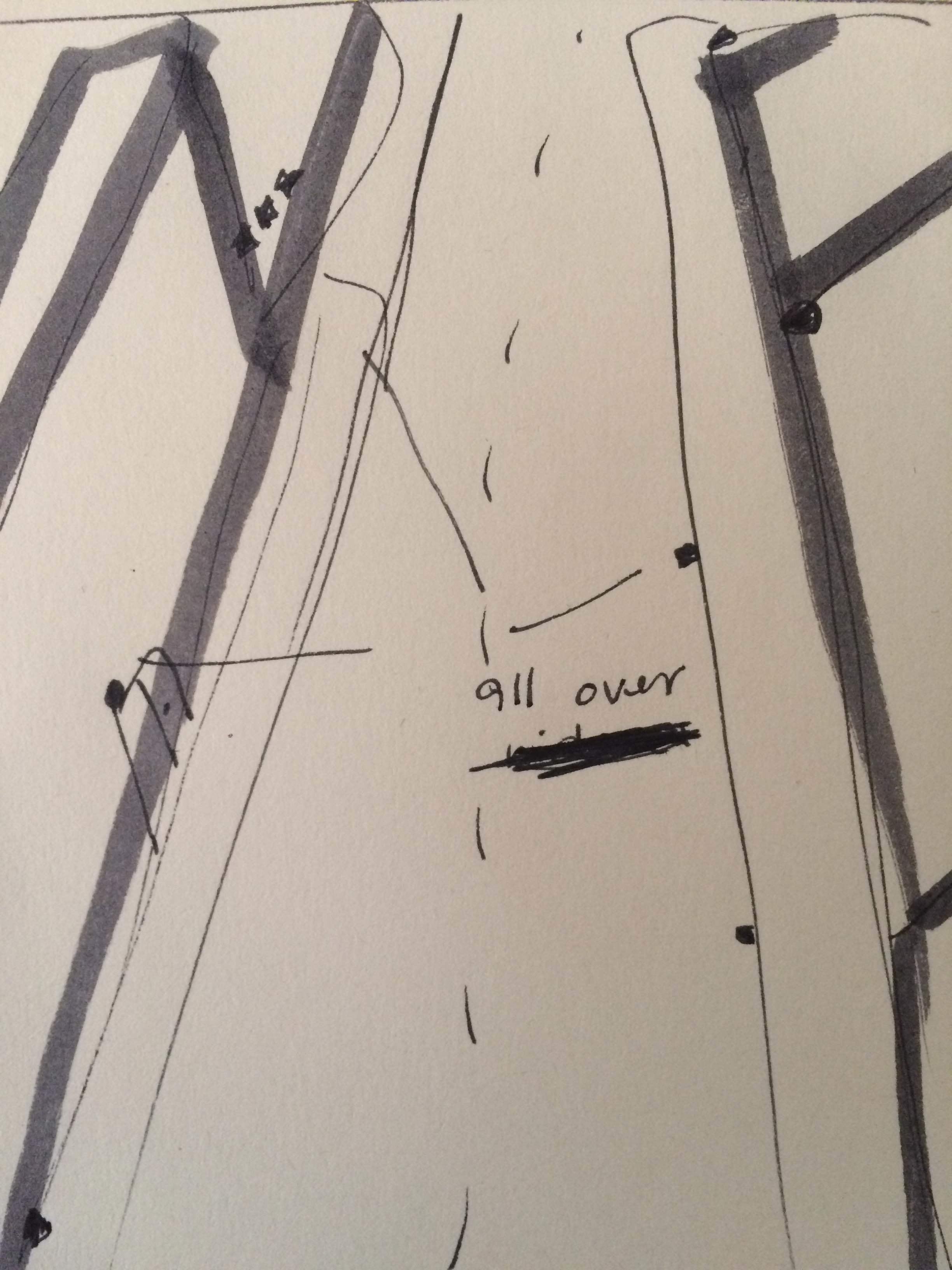

Bluck and Harley are still considering the formal arrangement of the brownstones in relation to the redline. Below are sketches of four permutations of the installation with a current preference for a combination of scenario #1 and scenario #2.

Clay model of a New York-styled brownstone to be cast in cotton fiber paper.

Model of New York-styled brownstone cast in cotton paper pulp.

Model of New York-styled brownstone cast in cotton paper pulp. Slightly translucent.

Model of New York-styled brownstone cast in cotton paper pulp.

video models of Horizon Line.

Models not to scale. The small clay pieces represent the paper cast brownstones.

Bibliography

"Redlining." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation.

Gold, Daniel M. "Review: ‘Class Divide’ Shows the Extremes Hypergentrification Creates in a Neighborhood." The New York Times. 12 Apr. 2016.

The Editorial Board. "The Racist Roots of a Way to Sell Homes." The New York Times. 29 Apr. 2016.

Wilder, Craig Steven. A Covenant with Color: Race and Social Power in Brooklyn 1636-1990. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.